TL;DR: The technology we have now isn’t an inevitable state of affairs, but has come from a long-term series of cultural choices. We still see short-term profit as the main aim of technology, which discourages other cultural views, lifestyles and priorities within the sector. But we can think about technology in terms of people more, and take active steps to break out of a monocultural loop.

This post is a set of personal reflections and follow-on thoughts following a fascinating workshop session. I’m hugely grateful to Hannah for inviting me along, and for kickstarting this post and this chain of thoughts.

Monday morning ☕

Honesty time - 9am on a Monday morning isn’t my usual time for discussing global challenges (or 8am even, taking clock changes into account). But here I am, coffee in hand and sunshine on the window sill. And, thinking about it, when is a good time? When do we actually sit down and make the time, space and energy to “think big” these days?

So I may be a bit groggy, but I’m also really appreciative, and intrigued, to be invited to this session. I’m checking in for a workshop titled “What Does a Sustainable Tech Industry Look Like?” being run by Hannah Smith as part of her Green Web Foundation fellowship.

It’s a great question to start the day with. And a bit more honesty: I have no idea.

Far futures ⏳

Sometimes a bit of morning grogginess and uncertainty can be a useful ally though. After introductions, we have a few minutes to think about how we’d like the future to shape up. Big question, and one that’s easy to overthink. I go with gut instinct which, to be honest (again), is often more authentic than a well-considered, over-wordy response.

In this case my three bullet points for utopia are:

- Co-operation and mutual recognition of shared humanity, even at a nation-state level.

- More relaxed - particularly around the need to have more, do more, and “be” more.

- Awareness and acceptance of problems, particularly around scale and complexity.

Spoiler: I’m not an inherent “fix the tech and all will be fine!” person, even though that’s where a lot of my current exploration is. My approach to human-scale challenges is from a place of curiosity and “depressurisation”: that is, a need to unpick the problem and allow people the space to reflect and address what comes up. Much like the workshop, in many ways. Setting aside an hour or two now can go a long way towards the next hundred years.

Technology does not exist 💾

Over the next couple of hours, we split into groups and use Kate Raworth’s Donut Economy model to guide us through the heady depths of the ongoing ecological crisis, and the role that technology plays in it.

Or, to be more precise, the tech workforce - this distinction in itself is an important point. “Technology” is too easy to dehumanise, to decouple and detach from the people involved in it: the decision-makers, the policy-setters, the makers and builders, the recyclers and the profiteers. Every time we talk about “tech” as a magical force, we’re embracing this notion that something uncontrollable - “innovation”, “markets”, “AI”, etc - is inevitable, and avoiding the idea that there are people running the show, or being affected by it all. Every time we use a buzzword or quotes, we’re avoiding the reality that people - no quotes there - are the main influencers, beneficiaries, and victims of the industry.

Realisation 1: Talk more about People Doing Technology, not Technology as its own thing.

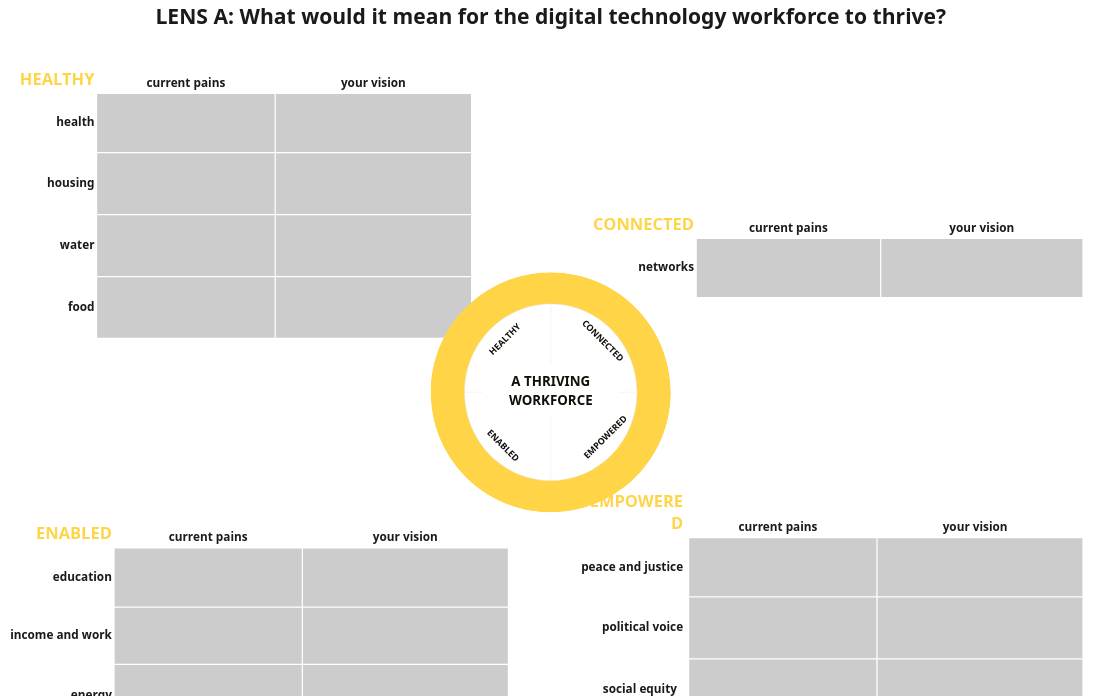

After this gentle intro, the session I’m in starts out by asking what it would mean for the “digital technology workforce to thrive”. It’s a question that deserves unpicking in its own right. Firstly, what do we mean by a “workforce” anyway? And secondly, what is “thriving”? Do we have a shared understanding or agreement about what either of those encompass? Do we need to shrink or expand any shared definitions? And if so, does that make the question easier or harder?

Answers to those are hard, though, and a little too much for now, perhaps. By the end of the session, however, we’ve mapped out some of the factors affecting the tech workforce more directly: training, pay, infrastructure, health and housing, and so on.

Below: Part of the framework used in the workshop session.

In one corner of the grid there is a section for “Empowerment”, which clusters together a lot of the social disparities in the workforce: pay gaps, representation, participation, and more. Looking around the rest of the grid though, it’s clear that this issue isn’t restricted to a single corner. Words such as “disparities”, “distribution”, “uneven”, “free”, “equal”, “for all”, and skills “not being widely taught” - these all get back to the same thing: A tech workforce cannot be healthy unless it integrates varying backgrounds and perspectives as much as possible. And an unhealthy tech workforce creates unhealthy technology, and vice versa.

Can we draw a clearer connection between the two at this point? I think we can. I just think we’re so used to “technology for technology’s sake” that throwing a discursive spanner in the works is not culturally A Thing. Yet.

Crunch is a cultural thing 😞

Take “crunch” in the videogame industry for example - the “need” for a team to work long hours and weekends to get a delivery done. It’s such a big issue that it’s got its own term. And yet, being overworked and stressed as deadlines loom clearly isn’t just a videogame problem, and definitely not a new thing. In some ways, alternative software development philosophies such as agile development are ways to re-think an industry’s approach to work, burn-out - and to expectations. Expectations about delivering “progress”, about what companies can expect of staff, and of what kind of life developers should be living.

But - as someone that’s trying to juggle working with looking after a family, a house, and mental health - I can tell you that there’s a big gulf between people who expect crunch and stress to happen, versus people that have enough stress already, and who would love a job doing that stuff, but no-thank-you to the extra, unnecessary pressure created by expectations.

And I use the term “unnecessary” deliberately. I have yet to see a technical project where delivery was improved by making your staff more stressed, or by throwing more people at it. Quite the opposite, in fact, and it’s depressing to see the same mistakes and anti-patterns repeating themselves decade after decade.

Why does that happen? How do those loops persist? Simple - we value, and optimise for, short-term outputs and gains. We aim to Get Things Done, at the cost of everything else. And there’s a feedback loop between achieving short-term gains, and attracting people who are able to devalue other things.

But when you’re pushed to choose between project delivery and looking after your family? Well, a lot of the time, the workforce environment just isn’t set up to optimise for that. Because, yes, it’s harder. It requires more thought, trickier decision-making, better structures and more communicatey comms.

Realisation 2: Talk more about the People not doing Tech, and why they’re not doing it.

Hypothesis time: Maybe there’s a reason tech-bro culture exists, and that’s because the young-white-male demographic is the easiest to coerce (for a variety of complicated reasons that desperately need unpicking) into capitalist values. Working hard and making money are still the narrative for success that we get taught, and that we buy into early on without much consideration.

But nobody interested in delivering things quickly is going to look into that. Values are hard. Culture is hard. A profit-making attitude, by default, optimises by taking hard things out and externalising them, from the ecological cost of action, to the political needs of a workforce with multiple perspectives.

Which brings us back to the donut model. Sustainability requires a constant balancing act to ensure the system doesn’t move too far in one direction or the other. That balance requires seeing the connections between things, and a choice to adjust direction as needed.

You broke it, you fix it 🪛

Everything is connected - supply chains, ideas, markets, communities. And yet the kicker is that we have to disconnect things in order to make progress. We disconnect people and politics in order to focus on delivery. We disconnect home life and diversity issues to focus on “simpler” solutions.

In some ways, any framework or approach which is employed to look into holistic, global challenges is inherently at risk of the same issues that any organisation or industry faces. To decide what to do, we map things out, carve them up, and simplify things so our human brains can work on one thing at a time.

Which is great. But there’s a fundamental issue that we forget about. While we’re pretty clever at breaking up a problem space, too often we forget to put the answers back together once we’ve come up with solutions. More often, the solutions become a whole new problem space of its own, and we descend into more and more granular challenges, ad infinitum.

In a similar vein, good coders know that writing code isn’t the end of the solution. Unit tests, source control, documentation, etc - all these form part of a larger social approach to problem-solving, the needs of the group rather than the individual computer or engineer.

But perhaps we can expand it out even further than just an engineering practice: To finish up the solutions properly, we need to connect them back up to people. As many people as possible, with as wide a set of needs and cultures as possible. Only then can we actually mark the deliverable as “Done”.

Realisation 3: Solving a problem isn’t the end of it: Solutions need spreading.

Some of the solutions put forward in the workshop go towards this ideal. One of my own notes for suggestion says “Deliberate cross-boundary diversity”. Alongside, someone else has posted “Politics for all”. All these thoughts get back to a sense of inclusion that a lot of us feel, in our gut, is missing from the world right now.

To simplify, we can squint a bit and see the world along a single dimension. In one direction, there is action that excludes, and maintains separation between people. In the other direction, there is action that actively includes people, and then maintains this inclusion.

Think through your team and its behaviours - where along this line do your daily behaviours fit in? Are your scrum stand-ups reinforcing delivery over attitudes and values? What about your recruitment processes and feedback routes? Even just taking a moment to reflect on these can be a powerful action.

Just the beginning 🚦

So a final bit of honesty: I’m still a long way from that right-side of the diagram on a personal level, and towards the actions that a more sustainable and diverse future needs. There’s a lot of inertia in the system right now. I do what I have energy for, but I’m still a mile off what I could be doing.

On one hand, that’s kind of depressing. On the other hand, I’m excited that there’s still a lot of opportunity and potential there. Learning is a series of realisations like the ones here. They’re not the first and they won’t be the last, for sure.

But these feel like good insights for 9am (or 8am) on a Monday morning, and there’s still a long week ahead.

Hello. My name’s Graham Lally and I’m passionate about re-thinking “technology” (oh hello quotes) for the generations yet to be born. You can find out more about me and what I’m up to at groundlake.org. I’m always up for a chat too, so if you’d like to get in touch, you can find me on Twitter, LinkedIn, or good old-fashioned e-mail.